ARTICLE Grappling with Israel Through it Arts: Students Explore Israeli arts to Foster Questioning and Connection

Introduction

“How do we educate school-age children to feel a sense of attachment to Israel and an appreciation for its extraordinary existence and accomplishments while at the same time help them cultivate their ability to think and dialogue critically and constructively about Israel’s government and its policies?” (Sandel 2018). Thus asked the leadership of Brandeis Marin Jewish day school in California, articulating a challenge facing Jewish educational institutions across the world -- now more than ever. The school responded to this profound need by developing a distinctive model for Israel education, one that uses Israeli arts and culture to invite sophisticated exploration of complex issues. For the sake of sharing insights with the field, this article analyzes how the school implemented such an approach, and how it can lead to a school’s fulfilling its vision of simultaneously connecting with Israel, fostering curiosity, grappling with challenges, promoting dialogue, and honoring multiple perspectives.

Context in the Field of Israel Education

The importance and challenges of teaching about Israel[1] existed long before October 7, 2023, but October 7th and its aftermath have magnified the urgency. Many Jewish students and adults have felt a seismic shift in their relationship with Israel, feeling pressure to withdraw into uniform-thinking circles and/or struggling with uncomfortable perspectives. Even before October 7th, many Jewish Day Schools in North America had the desire to teach their students about Israel in a way that both fosters a connection with the country and honestly explores its complexities.[2] This desire aligns with several scholars who have advocated for an approach that both is “accurate” and “foster[s] a sense of belonging” (Troy, 2023).

However, educators face significant challenges when trying to create such a program (Pomson and Deitcher, 2010; Zakai, 2011; Zakai, 2014). Many fear that exploring critiques about Israel may turn students against the country. They are concerned that “the goals of critical thinking and love [of Israel] could potentially work at cross-purposes” (Zakai, 2011, p. 245) and that introducing complexity “may alienate students” (Grant and Kopelowitz, 2012, p. 64). Others worry that mentioning controversial issues will disturb the school community which has conflicting views about Israel. Schools, therefore, may adopt a practice of “constructive ambiguity” (Pomson and Deitcher, 2010, p. 67) where they avoid discussing sensitive topics in the hopes of minimizing conflict. The schools instead focus on creating an emotional attachment to Israel through purely positive experiences, at the expense of instruction toward fostering skills and understanding.

Despite these well-meaning efforts at inculcating a connection to Israel, doing so in a vacuum, that is, while avoiding dealing with Israel’s complexities, can backfire. There are “dangers of teaching a whitewashed or mythic Israel.” (Zakai, 2014, p. 312). Students inevitably become aware, from sources outside of school, about complexities such as the interplay with the Palestinian narrative, leading students to believe that their own education is incomplete. They attribute bias to their teachers and mistrust their information (Pomson, 2012). Lacking nuance and dismissive of their own education, students may distance themselves from Israel, undermining the very goals that their day school educators had hoped for. As Grant explains, “If we focus only on the inspirational side, we run the risk of indoctrination on one extreme and alienation on the other” (2008).

Not only can an honest grappling with the complexities lessen alienation, but it may even lead to a more comfortable and more confident relationship with Israel (Reingold, 2022, and see the summary of ‘the complexity hypothesis’ in Sinclair et al., 2013), though others have argued that complexity and attachment are not related in this way (Hassenfeld, 2023). In addition to these possible benefits, teaching the complexities of Israel has inherent value in that accurate and honest knowledge is gained - a presumed goal of any educational endeavor.

In recent years, many Jewish educators have expressed a desire to teach Israel in an honest, positive, and exploratory manner. However, as Zakai points out, awareness is only the first step; what is needed is a “clear pathway” (2014, p. 310) and effective tools for practical implementation.

One school that has answered this call is Brandeis Marin, a kindergarten through eighth-grade independent Jewish Day School in San Rafael, California. Educators at Brandeis Marin have created and implemented a program that offers a distinct model for engagement with Israel in all its beauty and complexities. Brandeis Marin created a multi-faceted approach to achieve this openness and connection. One main facet is its use of Israeli arts and culture to invite sophisticated exploration of nuanced issues.

This idea of Israel “inspiration through the arts” was proposed by Gringras (2006) who suggested that Israeli popular arts can serve as “our most valuable educational resource” that can both “engage us in our guts” and “challeng[e] our thinking.” He continues that “Israeli arts bring us inside the dance, inside the passionate wrestling over the soul of this country, in such a way as to touch us deeply and infuse us with energy for the struggle.” Encounters with Israeli art were also a key component of the Davidson School of JTS’s semester in Israel program for training emerging Israel educators (Backenroth and Sinclair, 2013). The arts approach enables students to engage with authentic sources directly. This openness is especially important given the extent to which students crave honesty and resist the bias they perceive (Pomson 2012).

Brandeis Marin’s Israeli arts and culture approach invites students to embrace questioning, nuance, meaning, and connection. This study will examine the school’s arts exploration program as a model for addressing the challenges of meaningful Israel education.

About Brandeis Marin

Brandeis Marin is a kindergarten through eighth-grade independent, co-ed Jewish Day school located in San Rafael, California. It serves a community that is diverse religiously, culturally, politically, and socio-economically. According to the admissions director, approximately 25% of its students come from households where all the adults identify as Jewish, 65% from a Jewish/mixed-faith household, and about 10% are from other faiths (Welner 2023). There is great variation in practice even for those families that do identify as Jewish. The community is also varied in its political views, though leans heavily liberal/left (Pomson and Wertheimer, 2022).

The school’s mission statement emphasizes collaboration, questioning, project-based learning, diverse perspectives, and critical thinking in all subject areas. Within that context, the focus of its Jewish studies program is on “challeng[ing] students to ask good questions, value multiple perspectives and wrestle with ethical questions while nurturing their spirit to experience moments of awe in life.” Connecting to Israel is also a part of this mission, in that the school aims to “foster a sense of connection to the people and land of Israel as a source of spiritual and cultural inspiration” (Brandeis Marin, Our Mission). Head of School Peg Sandel emphasizes that “we are both pro-Israel and pro-critical thinking” (Sandel 2022) which, in their school, go hand in hand.

Methodology

This study on the Israel engagement program at Brandeis Marin was initiated as a documentation of a Covenant Foundation Signature Grant (Shapero, 2022). To provide a comprehensive analysis of the program for this academic article, I conducted a second and third round of data collection, which included: multiple in-depth interviews with critical school and program leaders, teachers, students, and participants; a review of school documentation such as internal curriculum documents, multiple years of grant proposals, and diverse school learning materials; and an extensive review of relevant academic literature. Qualitative data analysis was performed to extract essential insights for the field of Jewish education.

The Israeli Arts and Culture Program: Overview and Goals

Educators at Brandeis Marin have created a program that offers a distinct and effective model for Israel engagement. Their approach aligns with school’s overall goals of inviting questioning and critical thinking as well as the school’s commitment to Israel.[3] According to Peg Sandel, Head of School, a primary aim of its Israel education is to show that one does not need to choose between the “extreme ends of support and criticism,” but rather, one can “grappl[e] with some of the hard stuff” while still feeling connected and “excited.” This goal includes, but is not limited to, wanting “to arrive at a sense of attachment to the state of Israel that includes the perspectives and stories of Palestinians” (Sandel 2022) and includes also other complicated issues in Israel and around the world. She aims to teach that being pro-Israel and pro-questioning are compatible.

The school has designed an Israeli arts and culture program that provides a positive and authentic way for students to enter into mature dialogue on complex topics. Across grades and subjects, Brandeis Marin uses exploration of contemporary Israeli arts and culture as a path for students to develop a meaningful, personal relationship with Israel that simultaneously fosters questioning and connection. In this article, I describe the program’s method and impact for the sake of sharing its learnings with the field.

The Israeli Arts and Culture Program: Content and Method

The Israel arts and culture curriculum is dispersed across several grades and subject areas: It is constituted foremost as a weekly, full-year eighth-grade course entitled “Israel Art and Culture” and is also a key aspect of the school’s eighth-grade Israel trip. Additionally, it is embedded in various grades from kindergarten upward in specific units, integrated across subjects. Each area will be expanded upon below. Art and culture include digital media, sculptures, poetry, paintings, street art, performance, music, and more.

The Israel Art and Culture 8th-grade course: The most intensive experience with this approach is in the eighth-grade course specifically dedicated to Israeli arts and culture. This year-long, weekly course was developed by the school’s long-time art and Jewish studies teacher, Lisa Levy. In the course, students are exposed to multimedia art[4] on a variety of Israeli topics and use those to grapple, explore, and connect with Israel. For example, students were presented with a photograph by an Israeli artist depicting a man experiencing homelessness pushing a shopping cart with his son lying on top of the bags (See Figure A1). Similarly, as part of a unit on Israel’s national anthem, Hatikvah, students study not only the lyrics and music, but also visual art related to it. One illustration by Israeli artist Rutu Modan depicts a group of Israeli schoolchildren wearing blue and white singing the anthem, with one student with her mouth firmly closed.[5]

In each case, students use a school-designed “PaRDeS method” to personally react to and interpret the piece of art without knowing anything about the artwork’s creator or context. Adapted from classic Jewish textual interpretation, PaRDeS involves exploring a piece of art on four different levels. On the ‘pshat/surface’ level, students simply observe and describe the art. At the ‘remez/hint’ level, students zoom out to come up with any questions they feel the pshat hints at. On the ‘drash/inferencing’ level, the students look again at their pshatobservations through the lens of their questions and see what possible answers or meaning they can infer. Finally, at the ‘sod/hidden’ level, students use their imaginations to try to uncover deeper underlying meaning or the story the art is trying to tell.

Only after they have approached the piece of art directly through these four levels, are the students exposed to information about the artwork. In the case of the photo described above, students are informed of the title (“Abraham and Isaac”), the identity of the artist (photographer Adi Nes, who identifies as gay and Mizrahi), and the year of publication. Using their own interpretation plus this context allowed students to delve deeply, exploring issues such as the impact of sexual orientation and homelessness on youth in society. In the case of the Hatikvah illustration, students use the PaRDeS method and explore why some Israelis might or might not feel included in Hatikvah’s lyrics - such as those of various religions for whom Israel may or may not be part of their “nefesh yehudi /Jewish soul.”

In each case, the students’ final reflection is “What did I learn about Israel by exploring this piece of art?” (Levy 2022). As a bonus, sometimes the school has been able to arrange for the students to have direct communication with the artists themselves to ask them any questions.

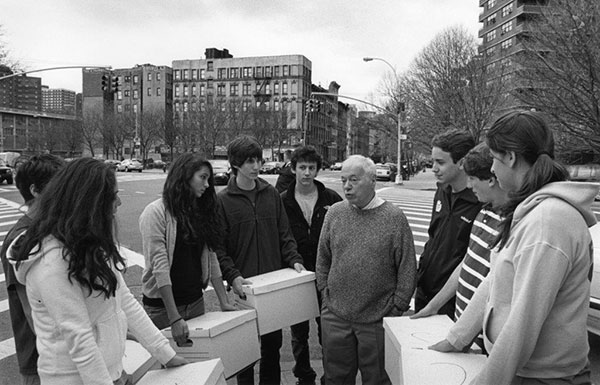

The 8th-grade Israel trip: During the Israeli Art and Culture course, the students also prepare to encounter Israeli street art during their eighth-grade Israel trip. Each student is assigned an Israeli street artist to explore deeply - their messages, background, and signature styles (such as the use of red string, or bandages, or certain characters. See Figures A2, A3, and A4). This project in and of itself allows the students to connect with Israel and explore complex issues. Then the students present to one another, thereby learning about multiple artists. Finally, during the trip, students look out for street art designed by artists they had learned about in the course.

The students are also invited to add their own personally-created stickers to the street art, a common practice of camaraderie among street artists. This sticker project is in collaboration with the middle school math teacher with whom the students design images according to mathematical principles and then create the stickers in the school’s Maker Lab. In subsequent years, the bus may return to the same spots, and students see not only the original artist’s stickers, but the previous years’ students’ stickers as well (see Figure A5), creating a Talmudic-like dialogue across the years. In this way, the students are invited into the conversation with the artists, with Israel, and amongst themselves. Additionally, the Israel trip includes two days of a Palestinian tour educator accompanying the Israeli tour educator, as part of the school’s efforts to teach a dual narrative and multiple perspectives. The school’s educators want students to hear voices from many communities in Israel that reflect the diversity of the country.

Israel through the arts is incorporated into other grades and subjects as well. For example, in fourth grade, students study maps and artistic representations of both California and Israel as part of their geography unit. The depictions are analyzed and interpreted in order to understand different perspectives on the regions and to invite conversation about borders, identity, and land (see Figure A6). The third-grade general studies unit about families uses photos of Israeli families of diverse structures, genders, religions, races, and ethnicities. While the unit is not exclusively about Israel, it makes young students aware of and normalizes the diversity that exists in Israeli society.

The use of Israeli art and culture is not ad hoc but is part of a coherent curriculum map. The school has identified for each grade its Israel themes and enduring understandings, aligned with both the overall grade-level theme as well as the spiraled Israel education curriculum. For example, in third grade, the grade-wide theme is “Community,” and the Israel theme is “Place: Communities, Cities, Towns, Villages, Kibbutzim, Moshavim, and Neighborhoods.” In fourth grade, the grade-wide theme is “Perspective,” and the Israel theme is “Place: Different perspectives through maps and borders” (Grantee Semi-Annual Report, January 2021). Furthermore, the themes are expanded into enduring understandings, such as, in fourth grade: “Different maps present different perspectives on Israel which can highlight or obscure the complexity of issues and diversity of perspectives present there” (Grantee Semi-Annual Report, July 2021). The project leaders and teachers have created an Israel education scope and sequence from kindergarten through eighth grade, building on itself and integrated with grade-wide themes.

The Israeli Arts and Culture Program: Impact

Using Israeli art and culture as the doorway to Israel engagement provides a safe atmosphere for deep questioning, curiosity, and critical thinking. It respects diverse perspectives and invites conversation. It serves as a tool to implement the theory of “teaching toward ambivalence” which “entails presenting and accepting that a wide range of views, understandings, and relationships with Israel are possible in American Jewish life” (Grant, 2023). It also creates a sophisticated and warm connection without preaching dogma, a connection that, the school hopes, will last far beyond graduation.

Preliminary evidence of such a post-graduation impact has already been seen. For example, alumni of Brandeis Marin had different attitudes toward Israel depending on whether or not the alumni had graduated just before or just after the new Israel curriculum was implemented: When the school held a reunion in November 2024, several of its alumni who had graduated in the years just prior to the school’s implementation of its new multivalent Israel approach declined the invitation. Many of these students stated that they “don’t feel Brandeis taught [them] nuance or presented the Palestinian side” and that they “are struggling and are feeling anti-Zionist” (Sandel 2024). They stated that in light of what they learned about Israel since graduation, they feel uncomfortable associating with their alma mater or any Zionist institution. In contrast, the graduates who had participated in the new Israel curriculum were more likely to attend the reunion and did not express anti-Israel sentiments even after the school inquired (ibid).[6]

Furthermore, when the head of school checked in with recent graduates, most of whom attend non-Jewish high schools, she found out that many of them were “leaning into these difficult issues - whether by supporting Israel, leading dialogue groups on their campuses between Zionists and anti-Zionists, and being ‘loud and proud’ Jews” (Sandel 2024). For example, one student taught a total of 38 fifteen-minute lessons - one for each class in her entire high school - explaining current events in Israel and Gaza (Sandel 2024). Another graduate heads the Jewish club at his high school, creating “belonging spaces” for Jewish students and leading discussions with Jews and non-Jews about Israel-related issues (Shaked 2024).

These results align with broader research described in the Context section above which concludes that “if we focus only on the inspirational side, we run the risk of … alienation” (Grant, 2008) and that modelling the welcoming of multiple perspectives may lead to a more comfortable and confident relationship with Israel (Reingold 2022).

A Brandeis Marin graduate of 2020 confirms the personal impact of learning about Israel through modern, varied Israeli arts: “Seeing all of this contemporary art from artists entirely different from one another,” has taught him “a powerful message about the strength that Israel has and the innovative, diverse people Israel is made up of” (Shaked 2024). The program also strengthened his personal connection to the land by allowing him to feel that “Israel is not just a place full of distant, biblical history, but one that students on the other side of the globe can relate to” (ibid).

The curricular focus on arts and openness also magnifies the impact of the 8th-grade Israel trip. According to its participants, it is not unusual for the tour bus to erupt in squeals when students recognize a familiar artist through their signature style. This enthusiasm can last after graduation: One mother of two alumni (Welner 2023) described how on a recent family trip to Israel, her children were thrilled to recognize the street art and stickers of artists they had studied years earlier in school. They took selfies and excitedly texted the photos to their former teacher and classmates.

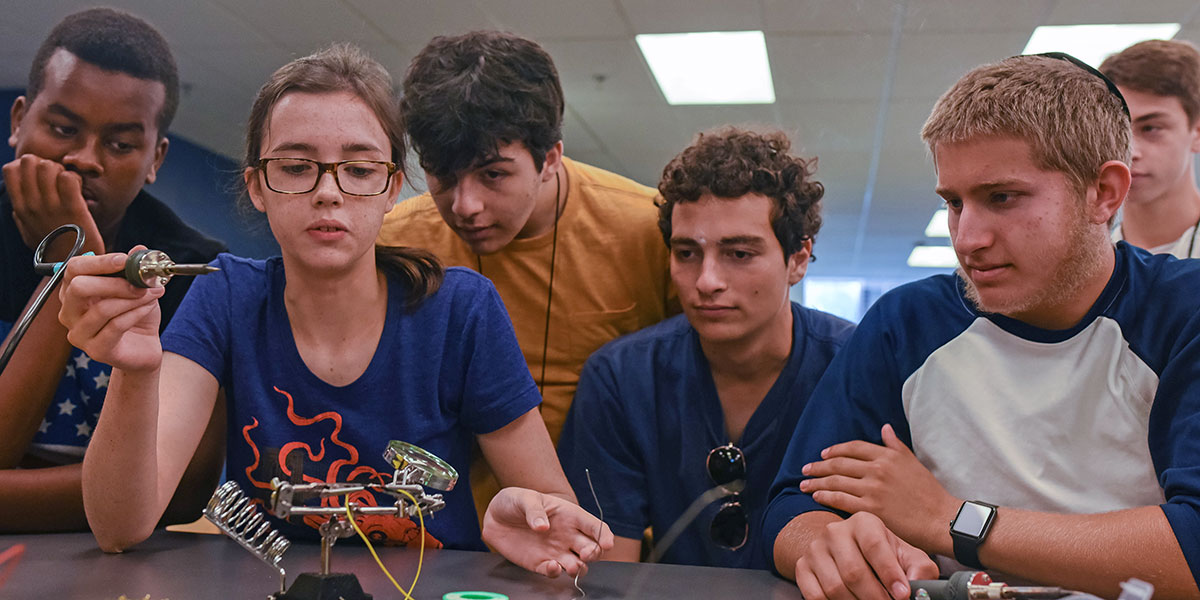

The school’s emphasis on warmly inviting questioning and critical thinking as part of its conversation about Israel is also recognized by the faculty. For example, a general studies teacher who participated in a faculty workshop on the topic was impressed and pleased to see that the critical thinking skills he encourages in his science classes were being applied to the topic of Israel as well (Seymour 2023). Participants in the faculty preparation for the Israel education program report that they learned how to enhance understanding on the topic, respect diversity, grapple positively with uncertainty, and have a safe dialogue on the issues related to Israel and beyond.

The school’s open exploration of diverse Israeli arts and culture supports its broader goal of modeling meaningful dialogue across differences for any difficult topic even beyond Israel. The school has applied its learnings from its Israel education to “leaning into other vital and hot topics such as nonbinary gender expression, the use of AI in education, and the Israeli judicial reforms controversy” (Sandel 2024). Likewise, graduate Shaked (2024) feels equipped “to be willing to have discourse on any topic with people who may or may not agree with [him]” and looks forward to continuing to do so when he attends college next year.

Graduates credit their experience in the school’s Israel education program with giving them the tools moving forward. Sandel explains that recent graduates explicitly “pointed back to their time here at the school and to our curriculum and to our approach, as having given them the confidence and nuance” (2024) to grapple and connect with Israel and to welcome uncertainty and dialogue. Recent graduate Shaked concurs that “Brandeis Marin is the reason I’ve been so forward in my Jewish role in my community and have been trying hard to not ignore conversations about the conflict around Israel. I feel that responsibility and that I’ve gained the skills that Brandeis taught me” (2024).

The Israeli Arts and Culture Program: Analysis of Impact

What qualities of exploring Israel through Israeli arts and culture might lead to this impact? For one, interacting with Israeli artists connects students with contemporary Israelis. Graduate Shaked describes that, due to the street-artist project, “I was emailing back and forth with my artist which was really neat, and my classmate got to meet up with her artist in Israel” (Shaked 2024). Shaked continues that he “would learn what people were thinking about in Israel.” Moreover, the approach feels authentic and immediate because it deals with primary sources.

In other words, having students directly interact with Israelis and primary sources created by Israelis invites students to feel camaraderie and trust, and to be insiders within the Israeli conversation.

The arts approach further fosters openness and connection by having students freely explore the cryptic art. Artwork invites curiosity and questioning because the messaging is open to interpretation. Students are not expected to provide the ‘right’ answer. Rather, they practice the skills of curiosity, multivalence, and developing their own opinions.

The arts program also models a simultaneously warm and critical thinking about Israel by providing examples of diverse Israeli artists’ and their varied perspectives on Israel. Students see and feel that multiple perspectives and questioning is encouraged and is a welcome part of connecting with Israel. In this way, open exploration of arts and culture provides an accessible, gratifying path to sophisticated exploration of challenging, complex issues.

This exploration at Brandeis Marin is designed to lead to what Grant and Kopelowitz have called “mature love,” a connection that is deep and that “can endure even in the face of … imperfection” (2012). The program’s focus on Israeli arts and culture neither avoids hard topics, nor lectures about them. Rather, it invites students to question, interact with, care for, and explore. Art can be a fertile ground for fostering nuanced connection because of its immediacy, its connection with real people (the artists), its provocativeness, its emotional pull, its excitement, its invitation to questioning, and its openness to a multiplicity of interpretations.

Conclusions

Brandeis Marin provides a model for addressing several obstacles that often face schools trying to implement meaningful Israel engagement programs. “In a lot of school communities, especially those where there is not a uniformity of thinking, there is a fear: Teachers and leaders feel ‘I don’t want to teach these hot-button, polarizing, supercharged issues because someone is going to disagree with what it is being taught, or how it is being taught’” (Sandel 2024). Indeed, if handled incorrectly, such a result may occur. However, if the hard topics are avoided or glossed over, this may lead to alienation, undermining the school’s very goals. Without creating an educational agenda that can “contain both commitment and critique” we are in danger of presenting our students with an “either-or choice” (Sinclair, 2013 p. 3), teaching our students that they must abandon one or the other. “To try to reduce it to a binary, to an either or, is to really sell ourselves short” (Sandel 2024). Brandeis Marin acknowledges and addresses these potential tensions by creating a “safe space” (Welner 2023) for questions and diverse perspectives. It communicates explicitly, both through its articulated vision statements and through its planned experiences, that complexity and lingering questions are a welcome and even essential part of caring for Israel.

While there has been some recognition in the field of the need to teach both ‘connection’ and ‘critical thinking’ about Israel, the two aspects are sometimes still taught separately, implying that they still conflict.[7] To solve this challenge, Brandeis Marin provides a practical curricular model for demonstrating that the two goals not only can be pursued simultaneously, but, in fact, are one and the same: It is precisely through consistently honest learning about the real, complex, vibrant Israel – in an Israeli arts-based, exploratory, and authentic way – that real and deep affection can be fostered.

The Brandeis Marin Israel education program is still a work in progress and its educators emphasize that they hope to continue learning how to further enhance the achievement of their Israel engagement goals. They have already made tweaks to the program described above and it remains in a constant state of evolution. They plan to continue devoting time and resources to faculty collaboration, mission-aligned curriculum writing, and reflection, demonstrating that intentionality, dedicated resources, and a growth mindset are additional important factors in creating meaningful Israel education.

The Brandeis Marin approach shows how an Israel engagement program can be designed in alignment with a school’s vision of connecting with Israel, fostering curiosity, supporting diversity, and grappling with challenges. It teaches that questioning and living with ideas in tension are a welcome part of the conversation of caring about Israel. It models that critical thinking and feelings of attachment are not in opposition; rather, through open and honest dialogue and through well-designed interaction with Israeli-arts-based, authentic, diverse, and invigorating sources, both critical thinking and mature connections are revealed as identical and are thereby enhanced simultaneously.

Judith Shapero

Judith Shapero is a senior educational leader, consultant, project director, and researcher. Judith has designed and taught Jewish Studies and Jewish Education courses at York University and at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, and has been Principal, Vice Principal, curriculum developer, teacher, and Department Head at TanenbaumCHAT and other schools in the Toronto area. Judith conducts evaluations of Covenant Foundation Signature grantees and is also the Director of Education at Temple Sinai Congregation of Toronto. Judith coaches many schools in the United States and Canada by leading faculty PD, creating custom curricula, supporting school leaders, and enhancing Jewish studies pedagogy.

Judith has won numerous awards for her contributions. These include the Division of Humanities Excellence in Teaching Award, the Shoshana Kurtz Book Prize, and the Joseph Zbili Memorial Prize in Hebrew from York University; the Gold Solomon Schechter Award for Jewish Family Education from USCJ; and the Charles H. Revson Fellows for Doctoral Studies, the Fannie and Robert Gordis Prize in Bible, and the Dr. Bernard Heller Graduate Fellowship from JTS.

References

Ariel, Y., Gringras R, Moskovitz-Kalman, E. (2011) Moving beyond hugging and wrestling. Contact, 14(1), 10.

https://steinhardtfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/contact_autumn_2011.pdf

Backenroth, O. and Sinclair, A. Reveling and Unraveling in the Face of Israel's Complexity. EJewish Philanthropy, 29 Aug. 2013, https://ejewishphilanthropy.com/reveling-and-unraveling-in-the-face-of-israels-complexity/.

Bandaid, A. (2015) High Roller [Street art], Tel Aviv, Israel. https://www.dedebandaid.com/bandaids-2

Brandeis Marin. Our Mission. https://www.brandeismarin.org/about/our-mission

Darian, A. (2013), The Jerusalem Map. [Ceramic, street art] Jerusalem. Photographed by Lisa Levy.

Davis, B. and Alexander, H. (2023). Israel education: A philosophical analysis, Journal of Jewish Education, 89:1, 6-33, DOI: 10.1080/15244113.2023.2169213

Gelfman, M. (2015). Healing scars, [Street art]. Tel Aviv, Israel. https://www.mayagelfman.com/

Grant, L. (2008). Sacred vision; complex reality: Navigating tensions in Israel education. Jewish Educational Leadership, 7(1), 2-22.

Grant L. and Kopelowitz, E. (2012). Israel education matters: A 21st century paradigm for Jewish education. Center for Jewish Peoplehood Education.

Grant, L. (2023). Formative Tensions: Old-New Paradigms in Israel Education, Journal of Jewish Education, 89:1, 46-52, DOI: 10.1080/15244113.2023.2169500

Gringras, R. (2006). Wrestling and hugging: Alternative paradigms for the Diaspora-Israel relationship. Paper written for Makom, Israel Engagement Network. www. makomisrael. net.

Hassenfeld, J. (2023). What's love got to do with it: Reevaluating attachment as the goal of Israel education, Journal of Jewish Education, 89:1, 75-81, DOI: 10.1080/15244113.2023.2169514

Kiss, J. (formerly Jonathan Kis-lev) (2014). The Peace Kids, [street art]. Tel Aviv, Israel. Photographed by Lisa Levy.

Levy, L. (2020). Brandeis Marin student sticker art, [photograph]. Tel Aviv, Israel.

Levy, L. Founding teacher of Israel through the arts, Brandeis Marin. Personal interviews. March 2, 2022, Feb. 10, 2023.

Modan, R. (2007). [Illustration]. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/18/opinion/18lebor.html

Nes, A. (2004). Abraham and Isaac [Photograph]. http://www.adines.com/content/biblical/Abraham&Isaac.htm

PaRDeS Art Analysis. Internal curricular document. Brandeis Marin.

Pomson, A. (2012). Beyond the B-Word: Listening to high school students talk about Israel. In L. Grant & E. Kopelowitz (Eds.), Israel education matters: A 21st century paradigm for Jewish education. (pp. 92-102). Center for Jewish Peoplehood Education.

Pomson, A. and Deitcher, H. (2010). Day school Israel education in the age of Birthright, Journal of Jewish Education, 76(1), 52-73.

Pomson, A. and Wertheimer, J. (2022). Inside Jewish day schools: Leadership, learning, and community. Brandeis University Press.

Pomson, A., Wertheimer, J., & Hacohen-Wolf, H. (2014). Hearts and minds: Israel in North American Jewish day schools. New York, NY: AVI CHAI

Reingold, M. Secondary Students’ Evolving Relationships and Connections with Israel. The Social Studies, vol. 113, no. 2, Mar. 2022, pp. 53–67.

Sandel, P. (2018). Tiferet Project Covenant Foundation Grant Proposal. Brandeis Marin.

Sandel, P. Head of School, Brandeis Marin. Personal interviews. Nov. 10, 2022. Feb. 9, 2023, May 7, 2024.

Semi-Annual Report to the Covenant Foundation. (January 2021) Brandeis Marin.

Semi-Annual Report to the Covenant Foundation. (July 2021) Brandeis Marin.

Seymour, R. Science teacher, Brandeis Marin. Personal interview. Feb. 24, 2023.

Shaked, Ari. 2020 student graduate, Brandeis Marin. Personal interview. May 17, 2024.

Shapero, J. (2022) Brandeis Marin Israel Education Project Documentation. Covenant Foundation.

Sinclair, A. (2013). Loving the real Israel: An educational agenda for liberal Zionism. Ben Yehuda Press.

Sinclair, A., Solmsen, B., & C. Goldwater. (2013). The Israel educator: An Inquiry into the Preparation and Capacities of Effective Israel Educators. The Consortium of Applied Studies in Jewish Education. https://www.casje.org/sites/default/files/docs/the-israel-educator.pdf

Stavsky, S. Jewish studies teacher and Israel trip coordinator, Brandeis Marin. Personal interview. Jan. 21, 2023.

Steinberger, M. Dean of Hebrew and Jewish Studies, Brandeis Marin. Personal interview. Feb. 3, 2023.

Troy, G. (2023) Identity Zionism as a Mature Zionist Approach to Israel Education, Journal of Jewish Education, 89:1, 67-74, DOI: 10.1080/15244113.2023.2174316

Welner, P. Admissions Director and mother of alumni, Brandeis Marin. Personal interview. Jan. 31, 2023.

Zakai, S. (2011). Values in tension: Israel education at a U.S. Jewish day school. Journal of Jewish Education, 77(3), 239-265.

Zakai, S. (2014) My heart is in the East and I am in the West: Enduring questions of Israel education in North America.” Journal of Jewish Education, 80:287-318.

Zakai, S. (2023) The Philosophies of Israel Education, Journal of Jewish Education, 89:1, 1-5, DOI: 10.1080/15244113.2023.2174738

Appendix

Works of Israeli art described in the article

Figure A1. Adi Nes’ photograph Abraham and Isaac (2004).

Figure A2. Maya Gelfman’s, Healing scars street art (2015), Tel Aviv.

Figure A3. Dede Bandaid’s High Roller street art, (2015) Tel Aviv.

Figure A4. Jon Kiss’s The Peace Kids street art, (2014), Tel Aviv, Israel. Depiction of the cartoon characters Srulik and Handala, representing Israeli and Palestinian national identity, respectively.

Figure A5. Photo of street art “stickering” showing a Brandeis Marin student-created sticker (bottom) from the school’s Israel trip in 2017 with a new added student sticker from 2020 (top). Photographed by Lisa Levy.

Figure A6. The Jerusalem Map, a modern recreation of the 16th century Bunting Clover Leaf Map of the world with Jerusalem at its center. Created by Jerusalem artist Arman Darian in ceramic, 2013, Jerusalem. Photograph by Lisa Levy.

[1] Readers interested in various theories of Israel education are encouraged to consult the Journal of Jewish Education’s March 2023 special issue on The Philosophies of Israel Education.

[2] For a discussion and critique of the term “complexity” in Israel education, see Hassenfeld, 2023 and Davis and Alexander, 2023

[3] One of the school’s core pillars is that its “Jewish studies curriculum challenges students to ask good questions, value multiple perspectives and wrestle with ethical questions while nurturing their spirit to experience moments of awe in life. Our community fosters a sense of connection to the people and land of Israel as a source of spiritual and cultural inspiration” (Brandeis Marin, Our Mission).

[4] See Appendix for images of the Israeli art described.

[5] This illustration can be found in its original context at Modan, R. (2007). [Illustration]. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/18/opinion/18lebor.html

[6] These results are anecdotal and have not established causation. A quantitative longitudinal study would need to be conducted in order to confirm the trend and establish causation. Nonetheless, the students responding in contrasting ways to the reunion invitation had graduated only a a couple years apart from each other, leading to the possibility that their different experiences of Israel education was one factor in their different approaches to Zionism.

[7] Some educators have suggested that in younger grades, we teach simple love, then in older grades or in the later stages of education we introduce the ‘real’ complex Israel, or that perhaps we alternate lessons that aim for one goal or the other (described and critiqued in Sinclair, 2013 and Zakai, 2014). Likewise, Gringras has lamented that his model of “hugging and wrestling” (Ariel, Gringras, and Moskovitz-Kalman, 2011) has been misapplied in this way, as if we can deal with only one of the two approaches at any specific time, activity, or even institution. This separated, even if ultimately inclusive, curriculum may still accidentally convey to our students that the two goals of critique and connection remain in conflict and that a choice must be made between them.

Judith Shapero

Judith Shapero is a senior educational leader, consultant, project director, and researcher. Judith has designed and taught Jewish Studies and Jewish Education courses at York University and at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, and has been Principal, Vice Principal, curriculum developer, teacher, and Department Head at TanenbaumCHAT and other schools in the Toronto area. Judith conducts evaluations of Covenant Foundation Signature grantees and is also the Director of Education at Temple Sinai Congregation of Toronto. Judith coaches many schools in the United States and Canada by leading faculty PD, creating custom curricula, supporting school leaders, and enhancing Jewish studies pedagogy.

Judith has won numerous awards for her contributions. These include the Division of Humanities Excellence in Teaching Award, the Shoshana Kurtz Book Prize, and the Joseph Zbili Memorial Prize in Hebrew from York University; the Gold Solomon Schechter Award for Jewish Family Education from USCJ; and the Charles H. Revson Fellows for Doctoral Studies, the Fannie and Robert Gordis Prize in Bible, and the Dr. Bernard Heller Graduate Fellowship from JTS.